Static site generators

Static site generators, such as Jekyll, Hugo, and Sphinx, are one of the most common authoring and publishing tools used in docs-as-code scenarios. Static site generators build all the files for your website, pushing Markdown files into the layouts you define, running scripts to automate logic you need and more as they generate out HTML files. This section focuses exclusively on static site generators. In upcoming topics, I’ll also explore hosting and deployment options and hybrid documentation systems.

- What are static site generators

- Jekyll

- Hugo

- Comparing speed with Hugo with Jekyll

- Sphinx

- Gatsby

- MkDocs

- Docusaurus

- What about this or that tool?

- Tools for generating the OpenAPI reference

What are static site generators

Static site generators are applications that you can run on the command line (or potentially through some other UI) to compile a website from simpler source files. For example, you might have various files defining a layout, some “include” files (containing re-usable content), a configuration file, and your Markdown content files.

The static site generator reads your configuration file and pushes your content into the layout files, adds whatever includes are referenced (such as a sidebar or footer or re-used snippets), and writes out the HTML pages from the Markdown sources. Each page usually has the sidebar and other navigation included directly into the page (pre-built), as well as all the other layout code you’ve defined, ready for viewing online.

Additionally, static site generators can be used programmatically in build scripts that are run as part of a process on a server. This allows them to be leveraged in continuous delivery processes that are triggered by a particular event, such as a commit to a particular branch in a version control repository, or as part of a script.

With a regular content management system (CMS) like WordPress, content is stored in a separate database and dynamically pulled from the database to the web page on each user visit. Static site generators don’t have databases — all the content is on the page already, and nothing is dynamically assembled on the fly through PHP or other server-side scripting. All the pages on a static site were built prior to the browser’s request, enabling an instantaneous response; nothing changes dynamically based on the user’s profile (unless done with client-side JS).

Freedom from the database model makes static site generators much more portable and platform independent. You simply have a collection of text files. In contrast, moving from one CMS to another usually involves database migration, and the many database fields from one CMS don’t usually map cleanly to other databases, not to mention the unique server configurations and other infrastructure required for each solution. Static site generators remove that database and infrastructure complexity, making the text files lighter, more portable, and less prone to error from database and server issues.

Before I had my blog idratherbewriting.com in Jekyll, I used WordPress (and was even a WordPress consultant for five years as a side job). I can’t count how many times my WordPress blog went down or had other issues. I routinely had to contact Bluehost (my web host) to find out why my site was suddenly down. I religiously made backups of the database, applied security patches and hardening techniques, optimized the database through other tools, and more. And with all of this maintenance hassle, the site was extremely slow, delivering pages in 2+ seconds instead of 0.5 seconds with Jekyll. For my many WordPress clients, I often had to troubleshoot hacked databases.

With static site generators, when you’re developing content on your local machine, you usually have web server preview (such as http://127.0.0.1:4000/) provided through the static site generator. Many static site generators rebuild your site continuously in the preview server each time you make a change. The time to rebuild your site could take less than a second, or if you have thousands of pages, several minutes.

Because everything is compiled locally from text files, you don’t need to worry about security hacks into a database. Everything is a human-readable plain text file, from the content files you write to the application code. It’s also incredibly easy to work with custom code, such as special JavaScript libraries, advanced HTML, or other complex code you want to use on a page. You can author your content in Markdown or HTML, add code samples inside code blocks that are processed with a code-syntax highlighter, and more. The openness and flexibility of static site generators let you do what you want with them.

Most static site generators allow you to use a templating and scripting languages, such as Liquid or Go, inside your content. You can use if-else statements, run loops, insert variables, and do a lot more sophisticated processing of your content through this templating language.

Because you’re working with text files, you usually store your project files (but not the built site output) in a code repository such as GitHub. You treat your content files with the same workflow as programming code — committing to the repository, pushing and pulling for updates, branching and merging, and more.

When you’re ready to publish your site, you can usually build the site directly from your Git repository, rather than building it locally and then uploading the files to a web server. This means your code repository becomes the starting point for your publishing and deployment pipeline. “Continuous delivery,” as it’s called, eliminates the need to manually build your site and deploy the build. Instead, you just push a commit to your repository, and the continuous delivery mechanism builds and deploys it for you.

Although there are hundreds of static site generators (you can view a comprehensive list at Staticgen.com), only a handful of are probably relevant for documentation. I’ll consider these several here:

One could discuss many more — Hexo, Vue, Middleman, Gitbook, Pelican, and so on. But the reality is that only a handful of static site generators are commonly used for documentation projects.

Jekyll

I devote an entire topic to Jekyll in this course, complete with example Git workflows, so I won’t go as deep in detail here. Jekyll is a Ruby-based static site generator originally built by the co-founder of GitHub. Jekyll builds your website by converting Markdown to HTML, inserting pages into layouts you define, running any Liquid scripting and logic, compressing styles, and writing the output to a site folder that you can deploy on a web server.

There are several compelling reasons to use Jekyll:

- Large community. The Jekyll community, arguably the largest and longest-running among static site generator communities, includes web developers, not just documentation-oriented groups. This broader focus attracts more developer attention and helps propel greater usage.

- Control. Jekyll provides a lot of powerful features (often through Liquid, a scripting language) that allow you to do almost anything with the platform. This scripting capability gives you an incredible amount of control to abstract complex code from users through simple templates and layouts. Because of this, you probably won’t outgrow Jekyll. Jekyll will match whatever web development skills or other JS, HTML, or CSS frameworks you want to throw at it. Even without a development background, it’s fairly easy to figure out and code the scripts you need. (See my series Jekyll versus DITA for details on how to do in Jekyll what you’re probably used to doing in DITA.)

- Integration with GitHub and AWS S3. Tightly coupling Jekyll with the most popular version control repository on the planet (GitHub) almost guarantees its success. The more GitHub is used, the more Jekyll is also used, and vice versa. GitHub Pages will auto-build your Jekyll site (continuous delivery), allowing you to automate the publishing workflow without effort. If GitHub isn’t appropriate for your project, you can also publish to AWS S3 bucket using the s3_website plugin, which syncs your Jekyll output with an S3 bucket by only adding or removing the files that changed.

For theming, Jekyll offers the ability to package your theme as a Rubygem and distribute the gem across multiple Jekyll projects. Rubygems is a package manager, which means it’s a repository for plugins. You pull the latest gems (plugins) you need from Rubygems through the command line, often using Bundler. Distributing your theme as a Rubygem is one approach you could use for breaking up your project into smaller projects to ensure faster build times.

Although Jekyll was one of the first major static site generators, its popularity has waned, in part due to the lack of leadership and contributors in the open-source project (see Jared White’s controversial post, Jekyll and the Genesis of the Jamstack ). Additionally, Jekyll’s Ruby architecture gives us slow build times (compared to Hugo). Finally, even though Jekyll is supported by GitHub, GitHub is slow to roll in version updates, so even though Jekyll is up to version 4.x+, GitHub supports only version 3.9.0.

Although I use Jekyll for all my sites, if starting out today, I probably wouldn’t choose Jekyll, as I think it’s on the way out. That said, GitHub could up their support game, and Jekyll could continue for many years forward. The platform, especially Liquid syntax, is one of the easier ones to learn and work with.

Hugo

Hugo is a static site generator that is rapidly growing in popularity. Based on the Go language, Hugo builds your site significantly faster than most other static site generators, especially Jekyll. There’s an impressive number of themes, including some designed for documentation. Specifically, see the Docsy theme, the Learn theme and this Multilingual API documentation theme.

As with Jekyll, Hugo allows you to write in Markdown, add frontmatter content in YAML (or TOML or JSON) at the top of your Markdown pages, and more. In this sense, Hugo shares a lot of similarity with Jekyll and other static site generators.

Hugo has a robust and flexible templating language (Golang) that makes it appealing to designers, who can build more sophisticated websites based on the depth of the platform (see Hugo’s docs here). Go templating has more of a learning curve than templating with Liquid in Jekyll, and the docs might assume more technical familiarity than many users have. Still, the main selling point behind Hugo is that it builds your site quickly. This speed factor might be enough to compensate for the steeper learning curve.

It’s also worth noting that Go is a language developed and supported by Google, and the Docsy theme theme also has a group of enthusiastic supporters, many of whom are Googlers who needed a publishing framework for many of the open-source tools like Kubernetes, Kube Flow, and gRPC. Because of this support from Google, Hugo might have more longevity than other static site generators that seem to be hobby projects from solo developers.

Comparing speed with Hugo with Jekyll

Build times may not be immediately apparent when you first start evaluating static site generators (often using small projects as tests). You probably won’t realize how important speed is until you have thousands of pages in your site and are waiting for it to build.

Speed here refers to the time to compile your web output, not the time your site takes to load when visitors view the content in a browser. Most static site generators load the pre-built pages quickly (less than 0.5 seconds), but the time it takes for the files to compile into a website before they’re deployed depends on the platform, the number of pages, and the complexity of the code on the pages.

Although it depends on how you’ve coded your site (e.g., the number of for loops that iterate through pages), in general, I’ve noticed that with Jekyll projects, if you have, say, 1,000 pages in your project, it might take about a minute or two to build the site. Thus, if you have 5,000 pages, you could be waiting 5 minutes or more for the site to build. The whole automatic re-building feature becomes almost irrelevant, and it can be challenging to identify formatting or other errors until the build finishes. (There are workarounds, though, and I’ll discuss them later on.)

If Hugo can build a site much faster, it offers an advantage in the choice of static site generators. Smashing Magazine recently chose Hugo and built a variety of complementary tools for managing their site.

For a detailed comparison of Hugo versus Jekyll, see Hugo vs. Jekyll: Comparing the leading static website generators. In one of the comments, a reader makes some interesting comments about speed:

Our documentation is about 2700 pages…. Generating the whole site takes about 90 seconds. That’s kind of annoying when you’re iterating over small changes. I did a basic test in Hugo, it does it in about 500ms.

This build time is a serious speed advantage that will allow you to scale your documentation site in robust ways. The author (whose docs are at https://docs.mendix.com) made the switch from Jekyll to Hugo (see the doc overview in GitHub). His switch suggests that speed is perhaps a primary characteristic to evaluate in static site generators.

The deliberation between Hugo and Jekyll will require you to think about project size — how big should your project be? Should you have one giant project, with content for all documentation/products stored in the same repo? Or should you have multiple smaller repos? These are some of the considerations I wrestled with when implementing docs-as-code tooling. I concluded that having a single, massive project is preferable because it allows easier content re-use, onboarding, validation, and error checking, deployment management, and more.

Regarding build speed, there are workarounds in Jekyll to enabling faster builds. In your build commands, you can limit the builds to one particular doc directory. For example, you can have one configuration file (e.g., _config.yml, the default) that sets all content as publish: true, and another configuration file (e.g., config-acme.yml) that sets all content as publish: false except for a particular doc directory (the one you’re working with, e.g., acme). When you’re working with that acme doc directory, you can build Jekyll like this:

jekyll serve --config _config.yml,config-acme.yml

The config-acme.yml will overwrite the default _config.yml to enable one specific doc directory as publish: true while disabling all others. Using this method, Jekyll builds lightning fast. This method tends to work quite well and is used by others with large Jekyll projects as well. Writers usually focus on one documentation directory at a time. If you have continuous delivery configured with the server, when it’s time to push out the full build (where publish: true is applied to all directories and no config-acme.yml file is used), the full build process takes place on the server, not the local machine. (The server might have other pipeline logic that validates, ingests, and deploys files as well, adding to the time.)

Although static site generators seem to change quickly, it’s harder for one tool, like Hugo, to overtake another, like Jekyll, because of the custom coding developers usually do with the platform. If you’re just using someone’s theme with general Markdown pages, great, switching will be easy. But if you’ve built custom layouts and frontmatter in your Markdown pages that gets processed in unique ways, as well as other custom scripts or code that you created in your theme specifically for your content, changing platforms will be more challenging. You’ll have to change all your custom Liquid scripting to Go. Or if working with another platform, you might need to change your Go scripts to Jinja templating, and so forth.

For this reason, unless you’re using themes built by others, you don’t often jump from one platform to the next as you might do with DITA projects, where all content usually conforms to the same specification.

Sphinx

Sphinx is a popular static site generator based on Python. It was originally developed by the Python community to document the Python programming language (and it has some direct capability to document Python classes), but Sphinx is now commonly used for many documentation projects unrelated to Python. Part of Sphinx’s popularity is due to its Python foundation since Python works well for many documentation-related scripting scenarios.

Because Sphinx was designed from the ground up as a documentation tool, not just as a tool for building websites (like Jekyll and Hugo), Sphinx has more documentation-specific functionality that is often absent from other static site generator tools. Some of these documentation-specific features include robust search, more advanced linking (linking to sections, automating titles based on links, cross-references, and more), and use of reStructuredText (rST), which is more semantically rich, standard, and extensible than Markdown. (See What about reStructuredText and Asciidoc? for more details around rST compared to Markdown.)

For continuous deployment with your hosting, Sphinx can be used with the readthedocs.com platform. Overall, Sphinx has a passionate fan base among those who use it, especially among the Python community. However, because Sphinx was specifically designed as a documentation tool, the community might not be as large as some of the other static site generator communities (which use the static site generators for building general websites, not just documentation sites).

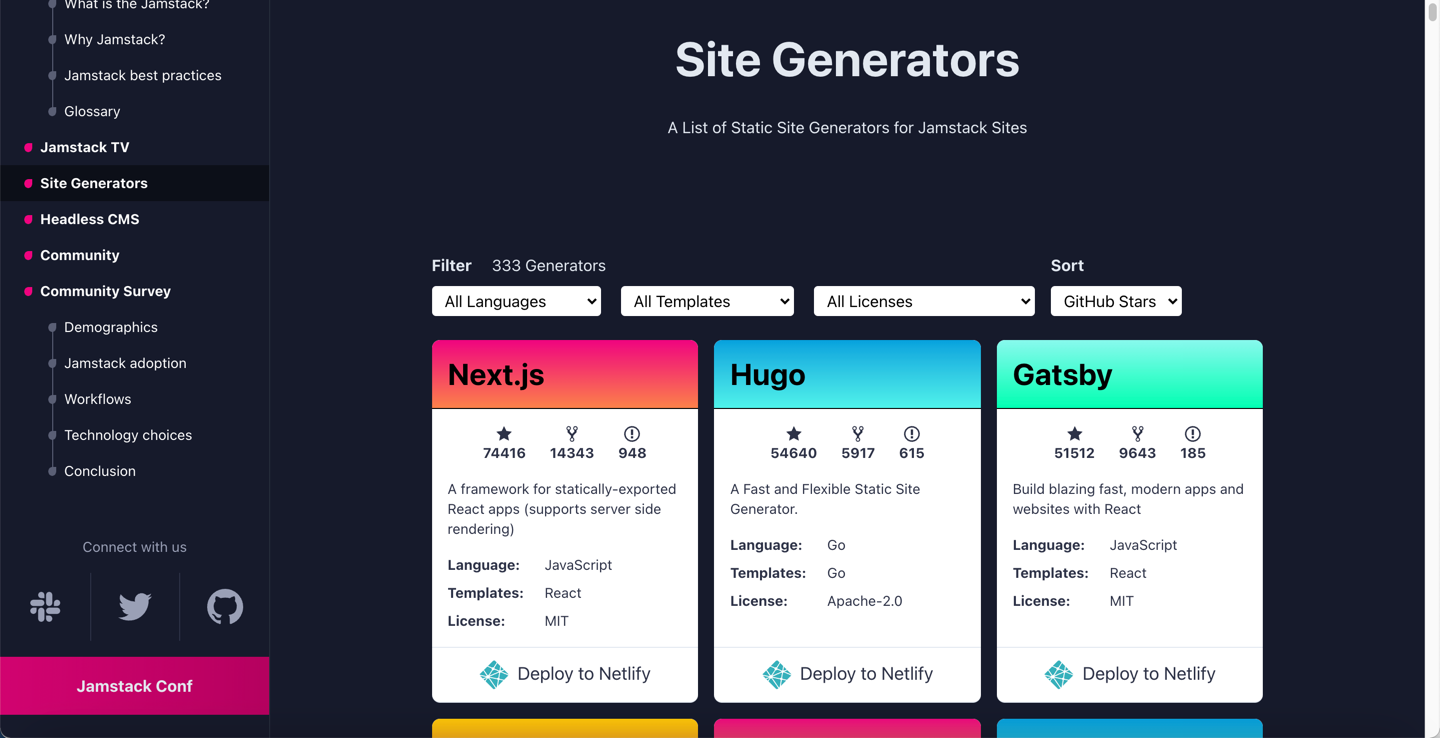

As of October 2021, Staticgen.com shows the number of stars, forks, and issues as follows:

On the Staticgen.com site, the star icon represents the number of users who have “starred” the project (basically followed its activity). The forked icon represents the number of repo clones that exist registered on their platform (GitHub, etc.). The bug icon represents the number of open issues logged against the project. To gauge how active the project is, browse the GitHub source and look to see how regular the commits are.

Next, Hugo, and Gatsby are the most common static site generators. If you look at Staticgen.com, you’ll see that between Hugo and Sphinx, there are many other more popular static site generators. But I called out Sphinx here because of its popularity among documentation groups and for its integration with Read the Docs. That’s what you have to keep in mind with static site generators — a particular option might be more popular, but for what purpose? Building general websites, or building documentation websites? Documentation websites tend to have unique needs and requirements (like a robust sidebar), so don’t be tricked by merely choosing the most popular options listed in staticgen.com.

Gatsby

Gatsby is a popular static site generator, and even offers a cloud-hosted version. However, Gatsby is more of an application static site generator than a pure static site generator that lets you write in Markdown and publish HTML. Gatsby appeals to React developers who are building more extensive web applications; the architecture and code in Gatsby tend to be more complex and confusing than the other simpler static site generators. I’ve met a number of people who experimented with Gatsby and then abandoned it (even though tech docs are still a primary use case for Gatsby). Other application static site generators similar to Gatsby include Next.js and Nuxt.js.

In selecting a static site generator, I don’t recommend using an application-based static site generator. You’re writing docs and primarily working in Markdown and HTML. You’re probably not building more extensive web app logic. You mainly want a tool that will take your Markdown and publish the HTML. Your company might want to create custom pipelines that push the published HTML into some other framework or system, and having a simpler static site generator will be advantageous in these scenarios. In general, stick with simple.

However, if your larger goal is to build a developer portal, with all the internal application logic (for example, API keys and developer profiles) that goes along with a portal, Gatsby might be the system your UX team chooses to use. Leveraging React components can speed development time, and some tools such as Redoc offer developer portals build on Gatsby. If the rest of your developer portal is built on Gatsby, it might be a sound choice for your docs as well.

MkDocs

MkDocs is a static site generator based on Python and designed for documentation projects. Similar to Jekyll, with MkDocs you write in Markdown and store page navigation in YAML files. You can adjust the CSS and other code (or create your own theme). Notably, the MkDocs provides some themes that are more specific to documentation, such as the Material theme. MkDocs also offers a theme (“ReadtheDocs”) that resembles the Read the Docs platform.

Some other themes are also available. MkDocs uses Jinja templating, provides template variables for custom theming, and more.

Although there are many static site generators with similar features, MkDocs is one more specifically oriented towards documentation. For example, it does include search. (You can incorporate Algolia search into any of these platforms, though, so built-in search — unless it’s really phenomenal — probably shouldn’t be a distinguishing factor.)

While it seems like orienting the platform towards documentation would be advantageous for tech writers, this approach might actually backfire, because it shrinks the community. The number of general web designers versus documentation designers is probably a ratio of 100:1. As such, MkDocs remains a small, niche platform that probably won’t see much growth and long-term development beyond the original designer’s needs.

This is the constant tradeoff with tools — the tools and platforms with the most community and usage aren’t usually the doc tools. The doc tools have more features designed for tech writers, but they lack the momentum and depth of the more popular website building tools.

Docusaurus

Docusaurus, built by Facebook, is also a popular static site generator oriented towards documentation needs. Docusaurus includes integration with Algolia for search, supports document versioning, translation, and more. The React foundation will also make it popular if you have front-end developers who prefer to work with React.

With support from Facebook, Docusaurus looks like a great option for a documentation website, and although I haven’t experimented with it myself, feedback from others has been positive. You can see how Docusaurus compares with other tools as well as look over their showcase. The showcase, which includes many doc sites such as Algolia, GraphQL, Redis, can give you an idea of how your doc site will look. Most themes have an attractive left sticky sidebar with collapse/expand toggles along with a right sidebar showing a floating table of contents.

What about this or that tool?

Right now there are probably many readers who are clenching their first and lowering their eyebrows in anger at the omission of their tool. What about … Docpad!!??? What about Nikola??!! What about Slate!! And Docsify?

Hey, there are a lot of tool options out there, and you might have found the perfect match between your content needs and the tool. Additionally, the tools landscape for developer docs is robust, complex, and seemingly endless. Most people don’t have deep exposure to that many tools. If you start with one and become familiar with it, changing course becomes harder. There often isn’t a killer feature that prompts you to refactor and recode your entire website.

And the winds seem to change from year to year. What may be relevant one day might be passé the next. Docs-as-code tooling is a difficult space to navigate, and selecting the right tool for your needs is a tough question. I offer more specific advice and recommendations in Which tool to choose for API docs — my recommendations. The tool you choose will affect both your productivity and capability, so it tends to be an important choice.

For more doc tools, see the Generating Docs list in Beautiful Docs. Additionally, DocBuilds tries to index some of more popular documentation-specific static site generators.

If you want to explore different API doc sites and analyze what tools they use, check out a Chrome extension called Wappalyzer. With this extension, you can easily see the underlying technologies for a site. It can help you detect trends and patterns with API tooling.

One pattern you’ll observe, as I noted in the overview to this section, is that few API documentation sites tend to use traditional help authoring tools. Yes, common documentation generators like Swagger, Redoc, and Stoplight are used, but for the bulk of the conceptual documentation, you’ll find a variety of tools used, with no dominant static site generator or architecture.

Tools for generating the OpenAPI reference

In this discussion on tools, I have purposely avoided diving deeper into tools that auto-generate out reference documentation from the OpenAPI specification. I cover these tools more in the OpenAPI spec and generated reference docs section. These tools include Stoplight, SwaggerHub, Redoc (all site sponsors, by the way), as well as Readme.com and DeveloperHub.io. For more of these tools, see Ultimate Guide to 30+ API Documentation Solutions from Nordic APIs and Tools and Integrations from Smartbear.

One drawback with tools that auto-generate out the OpenAPI reference is that their support for more conceptual documentation will likely be limited. Tech writers tend to spend the bulk of their time writing more conceptual docs; reference docs are often written and generated by engineering teams themselves. Even so, you will likely run into challenges with integrating the conceptual and reference docs into a seamless experience.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.

103/167 pages complete. Only 64 more pages to go.