API product overviews

The product overview tells your product’s story at a high level, including what you can do with the product, the market needs or pain points it solves, requirements to use it, who the product or other features are for, and other introductory information. A company with multiple products will have distinct product overview pages for each product, with a more general umbrella overview for them all. In contrast, smaller companies with fewer products might have a single, consolidated product overview page for everything the company offers.

Although a seemingly simple page, the product overview page can overlap into marketing domains, create redundancies with README’s, and pose challenges in connecting with a more diverse audience (both engineers and bizdev people) than the rest of your technical docs. Overall, the product overview is an area where documentation and marketing intersect in interesting ways. The product overview is one of the hardest topics to write, but it’s also likely the most important.

- Key questions a product overview should answer

- Presentation on product overviews

- Telling your product’s story

- Common use cases

- Product overview vs overviews (plural)

- Audience includes decision-makers

- Overlap with marketing

- Strategies for the documentation’s product overview

- Differences between marketing and documentation content

- Key differentiators in product overviews

- Overlap with README’s

- Good Docs project template

- Sample structure of a product overview

- Sample product overviews

- Activity with product overviews

- Summary of best practices for product overviews

- Reasons why product overviews are often minimal or nonexistent

- Cause 1: The reader isn’t the intended audience, so the overview fails for the reader

- Cause 2: UX’s influence on intuitiveness implies that long overviews indicate bad design

- Cause 3: Overview pages are hard to write, so they’re often neglected

- Cause 4: Agile’s co-development influence makes it difficult to surface higher-level content needs

- Cause 5: Higher-level content is already handled by developer marketing content, making it redundant in docs

- Cause 6: Tech comm buys in to the “reading to do” paradigm for docs, minimizing the need for longer conceptual docs

Key questions a product overview should answer

Too often with developer documentation, the documentation gets quickly mired in technical details without ever explaining clearly what the product is used for. It’s easy for writers to lose sight of the overall purpose and business goals of the API by getting lost in the endpoints and other technical details. Unfortunately, many documentation sites never seem to explain the story of their product, thus missing out on a foundational aspect of the documentation. The product overview should let users get a good understanding of the following:

- What does the product do?

- what are some examples where you’d use it?

- Who is it for?

- What problem does the product solve?

- How do you get started?

These are essentially who/what/when/where/why/how questions — not rocket science here, just the basic fundamentals of expository writing.

Keep in mind that there are thousands of APIs. If people are browsing your API, their first and most pressing question is, what information does it provide? Is this information relevant and useful to my needs? How does it differ from other products in this same space? The user’s first question is usually not “How do I configure this endpoint.”

Because the product overview is really one of the few places where you can tell a story, the product overview space should appeal to tech writers and be one of the content areas where we excel.

Presentation on product overviews

I recently gave a presentation on getting started tutorials and product overviews. You can watch the presentation here:

Telling your product’s story

To tell your product’s story, consider identifying a market need that your product solves. This is the basics of storytelling — there is some conflict that a protagonist (in this case, your product) addresses and solves. In The Top 20 Reasons Startups Fail, one of the main reasons startups fail is their inability to solve a market problem. The authors explain:

Startups fail when they are not solving a market problem. We were not solving a large enough problem that we could universally serve with a scalable solution. We had great technology, great data on shopping behavior, great reputation as a thought leader, great expertise, great advisors, etc, but what we didn’t have was technology or business model that solved a pain point in a scalable way. (CB Insights)

To encapsulate this overarching story, the product overview focuses on the market problem that the product solves. If the product doesn’t solve a market problem, that could be a red flag about the product itself. So the first step in the product overview is to describe the pain point your product solves.

Common use cases

To make the product’s market-solving characteristics more concrete, list some common use cases or business scenarios in which the product and API are relevant. These scenarios will give users the context they need to evaluate whether the API is relevant to their needs. Too often, product descriptions are general and high-level (e.g., “X product helps companies collaborate more effectively…”). These higher-level abstract descriptions fail to resonate with users.

Use cases are concrete examples of how the product might be used. Continuing with the above example, a use case might be “X product allows writers to work on the same document simultaneously through a remote browser interface,” or something. Usually, a product manager has already defined a list of key use cases for a product and would have these available.

Product overview vs overviews (plural)

A developer portal usually has documentation for many different products, not just one. Each product will have its own product overview page. In fact, the homepage of the developer portal rarely has a product overview. Instead, the developer portal’s homepage often serves as a routing board to the product overviews and other developer journeys.

Even a single product might have multiple overviews for each of the features. The overview is just a term for the opening page of a product, the landing page or starting page. Whenever you need a high-level description of your product, you need an overview page.

Audience includes decision-makers

One important dimension to keep in mind with product overviews is the expanded audience. Product overviews aren’t just read by your target documentation users, i.e., usually engineers. Product overviews are frequently read by product managers, executives, and other decision-makers who are trying to decide whether to purchase or move forward with the product. These decision-makers might be trying to size up the complexity of integration, how many person-hours the effort will consume, and whether the product will solve the problem they have. Only documentation can truly answer this question, not marketing material.

For example, a high-level executive might be trying to decide if implementing your product will require one-week integration effort by a single developer or a team of 50 developers working heads-down for six months. The product overview should give some indication of the development effort. Even if you don’t call out the estimated development time, by browsing through the tasks in the docs, it should become clear what level of effort is involved in implementing the product.

In the overview, the high-level executive will be less interested in the technical details and more interested in conceptual and bigger picture content. List out the main components involved in the system, followed by an architectural diagram and an explanation. Save the excruciating technical details for the inner pages of the documentation.

Overlap with marketing

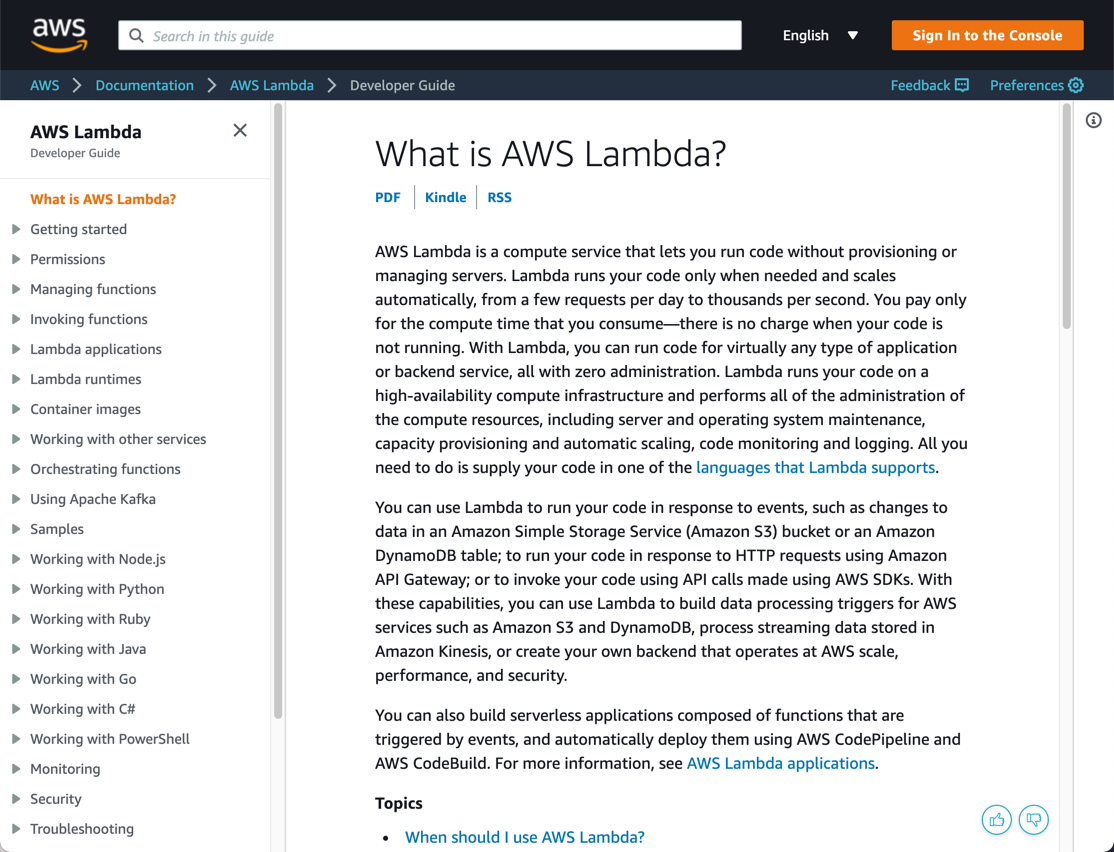

Another facet of product overviews is their frequent overlap with marketing content. In many organizations, there is a developer marketing group that handles higher-level product content, creating some overlap with documentation-based product overviews. For example, if you browse the AWS Lambda documentation, you’ll find that a higher-level product overview appears before the actual documentation. Here’s the marketing layer to the product:

This marketing layer covers these topics: Overview, Features, Pricing, Getting Started, Resources, FAQs, and Partners. The actual Lambda documentation is presented on another layer of the site:

If you read the first paragraph from each screenshot, you’ll see how similar yet different the two descriptions are. They repeat many of the same points but in different ways. The documentation product overview addresses these questions:

- When should I use AWS Lambda?

- Are you a first-time user of AWS Lambda?

Beyond the product description, in this Lambda example, the marketing content even has its own Getting Started page with tutorials, parallel to the documentation’s Getting started section, which is more robust.

Typically, developer marketing teams write the marketing product overview, while developer documentation teams write the documentation product overview. But as you can see, this is an area where content overlaps and where some coordination across teams becomes essential. Suppose the doc team for Lambda wanted to emphasize certain points that the marketing team did not — it would create a confusing transition between the two sets of content.

But even with differences, the idea is that business decision-makers read the marketing content, while engineers read the documentation content. Marketers are primarily writing for these decision-makers while tech writers are primarily addressing the implementers (engineers).

Your organization might have multiple teams writing content like this, or you might be tasked with creating both the higher-level marketing layer and the documentation yourself (especially in startups). In some ways, having a single team or writer handle both types of content might lead to a more streamlined, unified content experience. When you’re the sole writer, you’re less likely to repeat yourself in different places in contradictory ways. You can simply devote a section of your documentation to the marketing content rather than housing it on another site.

If you are stuck with the two-site model (marketing on one site, documentation on another), you could try to share content between these two sites, but usually marketing has a different system for managing and publishing content than the documentation teams. Marketers don’t usually adopt docs-as-code systems but rather prefer more CMS-driven systems. These systems rarely share content with each other, and even if they did, the marketing versions might be written using another style, perspective, or approach that contrasts with your docs, making it difficult to single-source the content. For example, I once tried to re-use marketing content (a product brief) that was written entirely in third-person point of view (“the partner does X”) rather than the traditional second-person point of view in docs (“you do X”). It didn’t work out well.

Strategies for the documentation’s product overview

What strategies should you implement when you’re faced with writing a product overview for docs, especially when a product marketing team has their own product overview on a separate site? Consider the following:

- Find out who the marketing group is and what messaging they are focusing on for the product.

- If marketing content already exists and you want to leverage it (rather than just link to it), consider creating a condensed/streamlined version of the marketing overview content, and point users to the marketing overview for more details. You don’t want to duplicate all the content because invariably, docs will go out of date as the other content evolves (not to mention the confusion of presenting two sets of overviews to users).

- Avoid copying any overblown promises about simplicity or ease of installation from marketing copy.

Differences between marketing and documentation content

Here it’s worth diving into some differences between documentation copy and marketing copy. While both genres might appear to share similar purposes in the product overview, avoid falling into marketing style in docs. For example, suppose you find a few pages of product descriptions that the marketing team already wrote, and you want to just copy it into the docs for the documentation product overview. Should you?

If you do this, strip out mention of the word “easy” or “just,” as in “the implementation is so easy, you just have to do X….” To sell a product, marketing often gravitates toward promises about ease of implementation. This is perhaps the hallmark of marketing content (from a tech writer’s perspective anyway). And many bizdevs or execs are trying to scope the difficulty of the implementation, so marketing’s message about ease of implementation makes sense.

But as a technical writer, you not only have an obligation to be honest about implementation complexity, you must also recognize that what is easy for one user might be insurmountable to another. (If you’ve ever done DIY projects at home, you know what I’m talking about.)

Never say something is “easy” — instead, you might qualify the degree of development effort based on the role. For example, you could say that for a seasoned engineer familiar with Java and who has been developing cloud-based apps for years, implementing this product will likely not require more than a week of integration effort. But for someone new to cloud-based app development or less familiar with Java, there will be a much steeper learning curve and might require several months or more of preparation and learning to implement.

If you can qualify the level of development effort based on different audience types, this will provide more realistic information. You can still answer the exec’s question — how difficult is this product to implement — without falling prey to promises of implementation ease.

By the way, it’s worth noting that most marketers have a superficial technical understanding of a product, so they usually cannot make judgments about the implementation difficulty anyway. They might be going off of an internal engineer’s observation that it’s “straightforward” or that it “should be easy to implement” or that “most engineers should find this familiar.” What the marketer might not realize is that engineers usually make these estimations by assuming the audience has the same knowledge level and background as the engineer. Unfortunately, most marketers remain within the pre-sales context and so rarely see the post-sales realities, where many support cases and threads spring up with confused and frustrated users.

Beyond adjectives about easiness, in the previous Lambda examples, the marketing copy uses terms like “virtually any,” “automatically,” “precisely,” and “favorite.” These superlatives aren’t usually used in documentation, which tends to be more factual and plain-speaking. Marketing tries to get users excited about a product by embracing these extreme adjectives, while documentation isn’t overtly trying to sell or hype anything.

Key differentiators in product overviews

As I’ve been arguing, the product overview space places you into murky territory where marketing and documentation blend. If you were to put on a marketing hat for a moment, what angle would you take in your writing (beyond language)?

Although it would be awesome to compare your product against competitor products, most likely your legal group will not allow it (mentioning competitors is usually taboo). And you might not have a deep understanding of other products to make a fair comparison. Or you might feel that readers will assume you’re too biased and wouldn’t trust your comparison anyway.

But what you can do is focus on your product’s key differentiators. These are features your product has that make it unique in the market. For example, maybe users can access your app from the browser rather than installing it locally. You don’t need to create a comparison chart showing how products X, Y, and Z lack online browser access. But by emphasizing this differentiating feature, you help establish a selling point and a potential reason for buying the product.

Remember that the product overview, unlike other documentation, often addresses a pre-sales scenario. As such, the reader is likely wondering how your product compares with other products in the same category. Why should they go with your product rather than another? What advantage does your product provide? Unless you know the competitive advantage of your product, you’ll have a difficult time writing marketing-esque content in your product overview.

Then again, you might want to leave that topic alone entirely and just point users to marketing material. You will need to make a judgment call about where marketing ends and where documentation begins. If you do try to veer into the marketing domain, however, reading through competitive analysis docs from marketers could help inform your writing.

Overlap with README’s

Another challenge with product overviews is the overlap with README content. A README is an introductory overview file (a homepage) placed in a code repository such as GitHub. The README often has many elements of an overview similar to a product overview in documentation site. If your documentation references a code repo, that code repo needs a README. But do you duplicate the same information in the README that you do in the documentation overview?

Hopefully not. The README might have a high-level summary and information about installation, configuration, and usage. But this information should be much more condensed/abbreviated than more detailed documentation.

Many guides about writing README content assume that the README is the only documentation for the code in the repo. As a professional technical writer, I rarely work on projects that are so small that the documentation can be handled by a single page that lives in a code repo. If that’s all you need for your product, great. However, chances are the README is only a glimpse of many more pages of configuration, installation, and usage detail that live in a more robust documentation site separate from the repo. If that’s the case, you might want to just link to your docs in the README.

Although the README and product overview overlap a bit, the README has some elements that don’t necessarily belong in regular documentation. Content elements specific to the README in the code repo might be the following:

- Code of conduct

- Contributor how-to protocol

- Filing issues

- Pull requests

- License information

- Team details/contributors

See The Essential Sections for Better Documentation of Your README Project by Thomas Parisot for a good guide about writing README content.

I admit that my preferences for the README might deviate from general recommendations from developers in this space. I am not a fan of duplicating the same information from the documentation into a README. Instead, I prefer to provide brief summaries only in the README and then point users to the main documentation for more details. For example, you could provide 1-2 sentences for each of the main sections and then point users back to your main docs for details. As a rule of thumb, a README might be the length of a poem while your docs are the length of a novel.

README’s have the additional complication of being difficult to maintain. Unless you have rights to publish to the code repository, it might be cumbersome to update the README content. If you’re an engineer who is writing the code and docs at the same time, this likely isn’t an issue. But in many organizations, technical writers are separate from engineering teams, and technical writers usually don’t publish code to GitHub repos. I’ve published to GitHub repos in the past (in an effort to speed along the publication of a sample app, I jumped through the hoops of the company’s approval process and pushed out the content into the repo), but later I regretted doing so. I learned that the person who pushes content into a repo owns that content and all the filed issues, pull requests, and other responsibilities that come with repo management. I didn’t want to be in that position — I wanted the engineers to own and maintain the code and control pushes to this space.

Overall, README files shouldn’t contain so many doc details that the information begins to conflict or become outdated with your main documentation. As long as you have only brief, condensed information in your README, it likely won’t go out of date with each release.

Good Docs project template

If you’re looking for more inspiration and guidance about product overviews, see the API overview template from the Good Docs project. They recommend similar sections as those I’ve been recommending here — establish who the docs are for, what problems the product solves, what market/industry the product is intended for, and so on. In the body of the overview, the Good Docs team recommends covering the following questions:

- What is it supposed to do? (What problem does it solve, and for whom?)

- What exact capabilities are available to the user? What services does it offer?

- What does it not do that developers should know about?

- What are the typical use cases?

- How does it work? (What do users need to know about architecture and internal components?)

- What dependencies does the developer need to know about before installing?

- What technical requirements do readers need? Include development environment and licensing requirements.

- What knowledge prerequisites does the developer need to know about before using the API?

(See The overview)

This is all good information to include. Consider auditing your overview by asking each of these questions. Does your product overview provide answers? If not, add a section that answers the question.

Sample structure of a product overview

Product overviews vary from product to product, but here’s the general flow that I like to follow:

- Description of the product

- Intended audience and assumptions about knowledge

- Sample use cases

- Requirements to use the product

- List of components

- High-level architectural diagram of components + explanation

- Development effort/scope

- How to get support/help

- Link to getting started tutorial

These topics don’t need to be standalone sections but can be interwoven into similar sections as you see fit.

At the end of the product overview, be sure to transition into the next logical step: getting started! Here’s where your getting started tutorial gets handed off to the user. It’s your call to action, so to speak.

Sample product overviews

Here are a few sample product overviews.

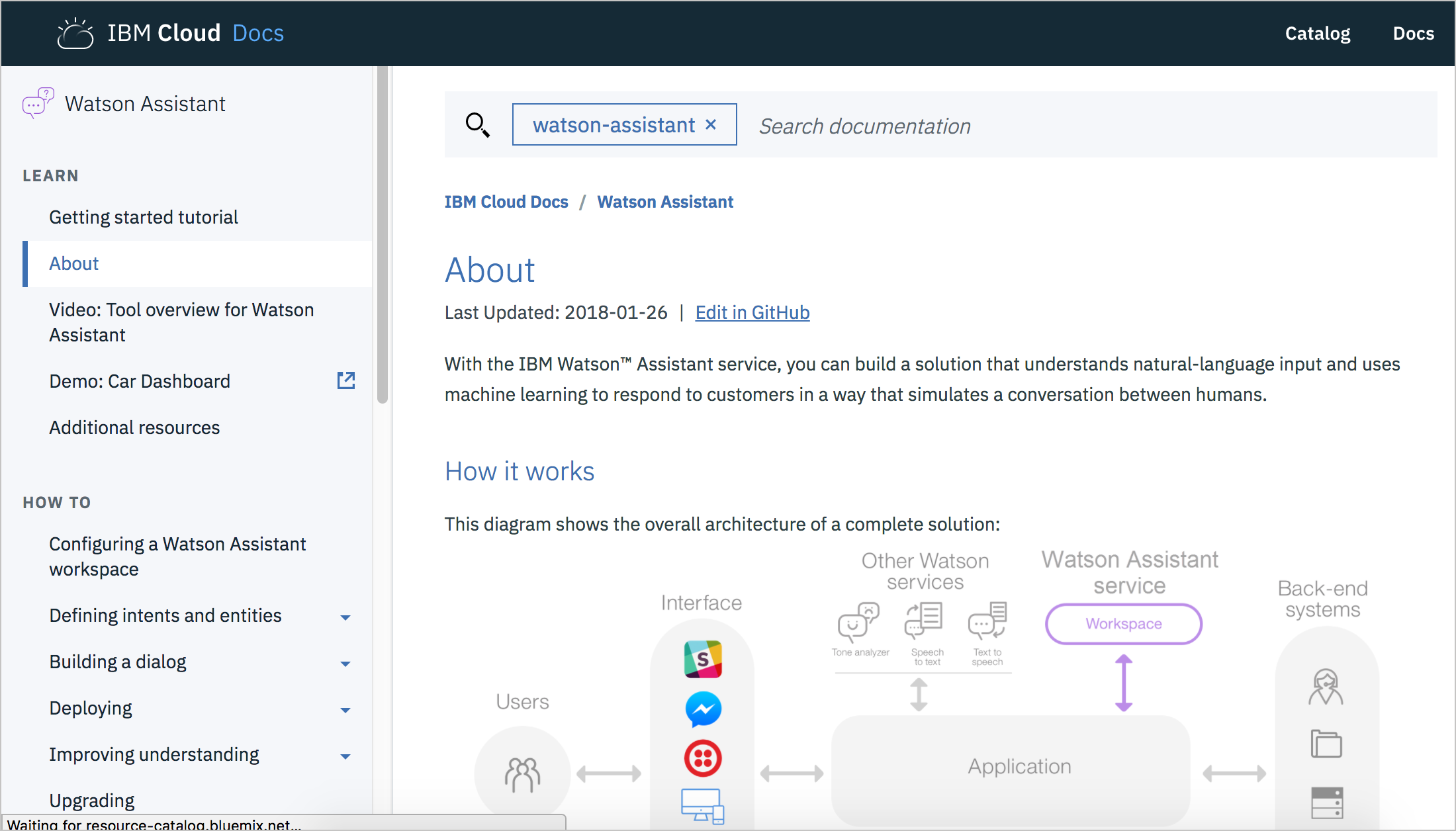

IBM Watson Assistant

IBM Watson Assistant starts off with a brief summary of the service, followed by a high-level diagram of the system and a summary about how to implement it. Including a diagram of your API gives users a good grounding about what to expect, such as the level of complexity and time it will take to incorporate the API.

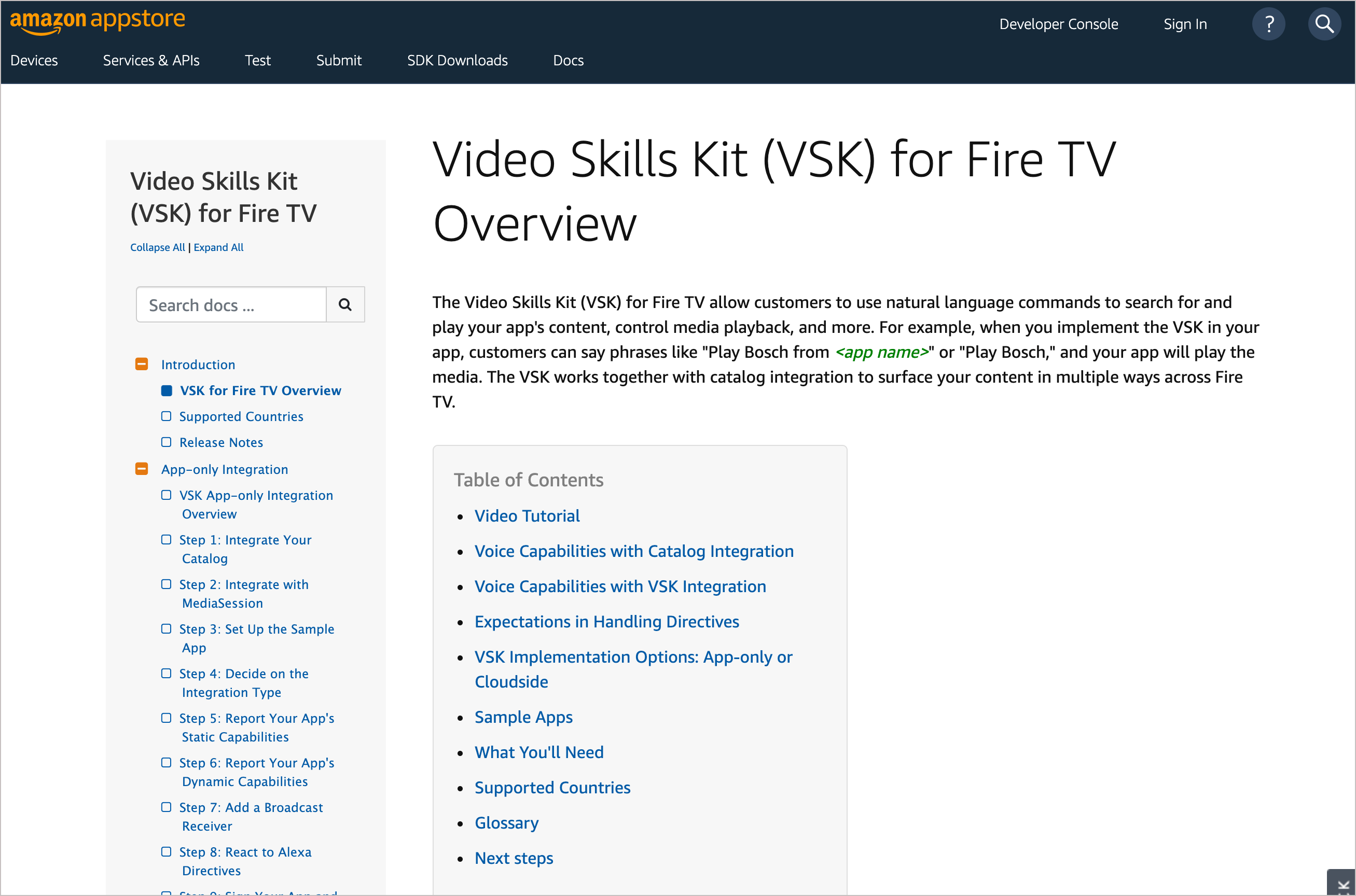

Video Skills Kit for Fire TV

This is an overview I wrote for a product called “Video Skills Kit for Fire TV.” The product overview stays at a high level by describing the capabilities the product provides, general implementation options, sample apps available, requirements to complete the implementation, supported countries, and next steps. There’s a parallel product overview page called Video Skills Kit for Echo Show.

Both of these product overviews are like product landing pages within a larger developer portal that covers many different products. In fact, if you go to the developer portal homepage, the page just routes you to different product overview areas.

Activity with product overviews

With the open-source project you identified, identify the API overview. Then answer the following questions:

- Does the documentation have a product overview?

- Does the overview clarify who the API is for?

- Does the overview indicate the market need or business problem the API solves?

- What questions do you still have about the API after reading the overview?

- How does the overview transition into a getting started tutorial or other first steps with the API?

Summary of best practices for product overviews

As a summary, consider including these general sections in a product overview:

- Description of the product

- Sample use cases

- Intended audience and technical level

- Requirements for use (system requirements, geo-requirements)

- List of components involved

- High-level architectural diagram of components, workflow

- Development effort and scope

- How to get support

- Most popular topics

- Known limitations, release notes

- Link to getting started tutorial

Every product seems to elicit its own unique sections on the overview, but these sections will give you a good starting point. Now let’s explore the reasons why product overviews frequently fail.

Reasons why product overviews are often minimal or nonexistent

Have you ever found yourself reading documentation for a product and wondered, what exactly is the product? What does it do? Who is this for? Why isn’t it more clear? You look for the big picture and higher-level understanding, but every topic seems to assume that you already know more than you actually do. The nature and use of the tool remains muddy.

In general, a product overview should allow users to get a good sense of what the product does, who it’s for, why they might use it, the pain point the product solves, requirements and availability, how to get started, how to get help when needed, and other foundational concepts. Ideally, the product overview should give you a solid understanding of the product and what it’s used for.

Yet in so many cases, when I start reading through documentation for a product, I’m often left confused and without a clear sense of what it’s for or how I might actually use it, let alone how to get started. Why are some product overviews so unfulfilling, so brief, disappointing, and weak? In this section, I’ll explore several reasons for anemic product overviews.

Cause 1: The reader isn’t the intended audience, so the overview fails for the reader

Perhaps the main reason that product overviews fail is because the reader (for example, a tech writer reading a product overview about some API for developers) isn’t the intended audience for the product. As such, the overview might fail for that particular reader but actually be fine for the intended audience. This mismatch of actual reader versus intended reader makes it difficult to make judgments about product overviews.

As an example, take a look at some of the product overviews in Microsoft’s Azure docs, which look exemplary to me. You could use any product as an example, but let’s start with the first product, the Anomaly Detector. The starting topic is What is the Anomaly Detector API?. (In fact, all docs seem to start out with “What is … [product]?” This frequent pattern creates a nice sense of predictability to the various doc sets in their portal.) The first two paragraphs start as follows:

The Anomaly Detector API enables you to monitor and detect abnormalities in your time series data without having to know machine learning. The Anomaly Detector API’s algorithms adapt by automatically identifying and applying the best-fitting models to your data, regardless of industry, scenario, or data volume. Using your time series data, the API determines boundaries for anomaly detection, expected values, and which data points are anomalies.

Using the Anomaly Detector doesn’t require any prior experience in machine learning, and the RESTful API enables you to easily integrate the service into your applications and processes.

Although the sentences seem clear, and there are screenshots, interactive demos, descriptions of features, getting started topics, and more, I’m still lost because I’m not the intended audience for the product. What is “time series data”? What kind of data is appropriate to analyze here? Why would I want to look for abnormalities in my data? What kind of application or process would I integrate this anomaly detection service into? I dunno…

As good as this product overview is written, it doesn’t make sense to me because I’m not the intended audience. I’m not a developer working with large data sets, nor am I involved in machine learning algorithms. I can’t even understand what scenario would make sense where I’d have “time series data” with anomalies that I need to detect as part of a machine learning model that I’m building, even though this scenario is apparently applicable across industries.

It’s not the writer’s responsibility to bring non-target users up from ground zero here, holding my hand through this knowledge domain and assuming I know nothing. But it would help to perhaps explicitly identify the audience here. Even without identifying the audience, though, it’s pretty clear reading this overview that I’m not the user envisioned for this product.

So how do you, as a technical writer, a person who is most likely an outsider to the domain you’re working in, know if the overview makes sense to the intended audience? This is the whole crux of writing documentation: most of the time, you’re an outsider to the knowledge domain, so it’s hard to know what the audience already knows or does not know, and what to explain or assume.

As technical writers, we usually spin our lack of domain awareness as a positive, because we don’t end up assuming our audience knows so much already. We aren’t hampered by the curse of knowledge, numb to the jargon and concepts our audience also isn’t familiar with. So we explain the basics, we define terms, we start a few rungs lower on the knowledge ladder than people expect. And users often appreciate it.

But without closer interaction with users, we can only guess what users might know or need to know. Typically, we end up relying on feedback from those who do interact closely with users (such as devrel groups). Through them, we try to better understand the user’s knowledge level, but even so, many times these groups can only speak from their own limited interactions. Most of us have experienced situations where engineers tell us that users will know this or that concept, only to learn later that users don’t and the assumptions confused them. At the end of the day, we find ourselves staring at a product overview and, even if it fails for us, we hope it works for the right audience.

As we read through product overviews, we have to remember that we’re usually not the intended audience. It might fail to orient us, but does it fail for the intended audience? At the very least, try to be clear about the intended audience in the overview, as this will set expectations for knowledge levels. You can also add a “Background Knowledge and Assumptions” section. This section could link out to some preparatory documentation (perhaps on other websites) that users should consult if they get lost.

Cause 2: UX’s influence on intuitiveness implies that long overviews indicate bad design

Another reason why product overviews are anemic is due to UX’s influence with intuitiveness. (This cause is related to the previous point but a separate facet.) The idea is that products should be intuitive and naturally address mental models that customers have, without the need for extensive explanations. Why would you need to explain a product in depth to the users who you built it for? If something needs a deep explanation, it probably isn’t well-designed and intuitive for that audience.

Achieving intuitiveness in your product is a common goal of UX design. In What makes intuitive products intuitive?, Scott Kitchell argues that a product is intuitive when it matches the mental model of the user. Scott says, “Intuitiveness can be created by designing every part of a product in reference to a mental model, and then promoting the mental model through the UI and marketing.”

Mental models are the logic and theories in our heads that make sense of the world around us. For example, in mountain biking, a common product for seats is a “dropper post,” which lets bikers dynamically raise or lower the seat post height by pressing a button on their handlebars. Why would one need such a button and the ability to quickly raise or lower the seat height while riding? If you’re into mountain biking, you know that climbing dirt/gravel hills requires you to sit low while keeping weight on the back tire for traction, so you might need to lower the seat quickly on the climb, but then revert to regular height for other scenarios.

In short, if you’re part of the intended audience, you already have a rationale for the feature and don’t need extensive conceptual docs explaining the scenario and reason for the product. You won’t see extensive conceptual docs for dropper posts on product detail pages. The need is already felt by the intended audience.

The problem in tech comm is that tech writers are usually outsiders to the domain, looking in at the product. We don’t share the same mental model as our users. As a result, many details don’t immediately make sense. Kitchell says:

Mental models are literally the logic within our heads, so if it’s in there, you’ll see the logic in it. From the outside however, others will not. Unintuitive mental models are like irregular looking blocks — They don’t fit well with other mental models which makes them harder to remember, and problem-solve with.

Ideally, the product should just make sense for users, without a need for in-depth explanation. If you don’t share the same mental model as your users, it’s difficult to assess how much users will actually need the who, what, and why of the product. It might just make sense to them based on their mental model and problem set, like a jigsaw piece that fits perfectly into the space for which the piece was created. To evaluate whether a product needs an overview, you have to evaluate it not from an outsider’s mental model, but from the mental model of users.

In some cases, your product might require some new learning even for the target user. Mark Baker says, “… learning is about rearranging our own mental furniture, finding our way through the thickets of our own minds. The expert can help us enormously at certain key junctures in that process, but most of it we simply have to do for ourselves” (Chatbots are not the future of Technical Communication). It’s not always the case that users will intuitively understand the product. Some learning frequently needs to take place, and that learning often involves some mental strain (the learning of a new model), even for the target audience.

For more on mental models, see the Schemas and learning section in Principle 5: Conform to the patterns and expectations of the genre and schemas Schemas are a more scientific term referring to the mental models in our heads that make sense of the world. See also Script theory in the same article. Script theory argues that if designers create experiences that match the schemas by which users operate, users will naturally know what to do and act in an almost scripted way. For example, Kirk St. Amant says if you design your hospital waiting room in an archetypical, expected way, then users will naturally know what to do when entering the space.

Define the stories that your audience uses to think about the scenario your product addresses. What mental model or schema organizes their thinking about the problem? If your product overview already naturally fits into this mental model, then you might not need to make the details more explicit in an overview — it might already make sense for the user.

Cause 3: Overview pages are hard to write, so they’re often neglected

Another reason product overviews often fail for users is because, put simply, product overviews are hard to write, and so they are often poorly executed. The product overview requires you to be thoroughly familiar with the product, comfortable enough to summarize the product at a high level, describe the overall architecture, use cases, how to get started, requirements and limitations, and more.

As technical writers, we’re often incrementing our understanding of a complex product little by little — we’re piecing together what it’s about, how it works, how to perform various tasks, the reference material about the APIs, and so on. We’re slowly identifying puzzle pieces and trying to fit them together into the right picture. At any given time, there are likely many unidentified and unused puzzle pieces, making our current picture incomplete. It might not be until several weeks or months that we have a light bulb moment and glimpse the full puzzle picture.

To use another metaphor, I often like to think of projects as a monster that I battle and slay. That moment when I slay the monster is when I unlock its secret and suddenly grasp how it ticks, how to unlock its data and have it returned to me. It’s at that point, near the end, that I can properly write the overview page. In general, I usually can’t finish the first page of documentation until I write the last page of documentation.

And when am I writing that last page of documentation? Sometimes right near crunch-time, about two weeks before release.

If you’re working more as an editor and publisher rather than an author, the overview might be even more challenging. You might be reliant on general product descriptions from internal documents, without the additional context and detail that you get by struggling with the product for months with hands-on exploration and experimentation.

Recognize that you typically acquire the full knowledge to write the overview only after you’ve written all the other documentation. To avoid last-minute efforts, keep running notes on an overview draft that you add to as you work through the other documentation. Place section holders on the page, and then fill them in as you go.

Cause 4: Agile’s co-development influence makes it difficult to surface higher-level content needs

Another cause for poor product overviews is agile’s co-development influence with products. Agile software development prescribes close interactions with users as software teams develop and build out the product. When users are so intimately involved in product development, essentially co-collaborators with each iteration, they don’t need the higher level overview, story, and purpose of the product. They need only the technical details for implementing it.

In Agile Principle 1: Active User Involvement Is Imperative, Kelly Waters lists out 10 principles of agile and says “active user involvement is the first principle of agile development.” Why is active user involvement so fundamental to agile development? User involvement is essential because software teams want to build the product in a way that matches users needs, and you can’t do that without closely working with users, checking in regularly with each build to see if it matches their expectations, and course correcting to fine-tune the alignment needed to build the right product.

But just as product team members become somewhat numb to product jargon and the reasons behind decisions, the docs follow somewhat the same suit. There’s no need to explain why the product is needed because, with active user involvement, these needs are communicated from the user from day one and throughout in regular meetings and other interactions. As such, there isn’t a strong need for this higher-level overview and understanding. The conceptual basis for the feature is already understood by users because the product team iterated with users to develop the feature.

Once the feature is complete, some brief technical docs get added that explain how to use the feature. But the feature itself, the reason it was created, the problem it solves, the high-level overview and description of the feature, etc., is not documented because the initial user didn’t need that high-level. The documentation likely follows a similar trend elsewhere, and soon you end up with lots of little building blocks and technical how-to’s but no higher-level descriptions and glue between all of these tasks. New users who didn’t participate in the feature’s development have to try to derive back what the feature is and why/what/who the product is for.

Product overview anemia is a byproduct of the agile development process itself. This is where a technical writer’s perspective as an outsider becomes so important. If you’re an outsider to both the product and domain, you won’t have this co-development history and won’t have seen the product evolve from a sketch on a napkin to a fully released product. You’ll see the lack of connecting glue between topics, the absence of a larger story that connects with your needs, and more. The problem is, without an audience asking for this higher-level information, you might be facing an uphill battle to generate the content. You might be writing an overview for an imagined future audience that hasn’t yet materialized.

If the users were co-developers of the product and features (or frequent sounding boards during the design phase), don’t use that group as a barometer for assessing content needs. Find someone who is new to the product.

Cause 5: Higher-level content is already handled by developer marketing content, making it redundant in docs

Another reason for anemic product overviews is because many of these higher-level questions are usually handled in the developer marketing layer, and tech writers don’t usually operate in that pre-sales space. In many doc portals, there’s a marketing layer that sits on top of the documentation. This marketing layer is supposed to articulate the larger story of the product — the problem the product solves, the target audience, use cases, case studies, and more — to a pre-sales audience.

As an example, see the example with AWS Lambda that I explained in the product overviews topic. In fact, the product overviews in the marketing layer pose challenges for overviews in technical documentation because tech writers usually try to avoid redundancy. Since many tech writers assume the marketing layer handles this larger story and overview about the product, this type of content is often absent or minimized in the documentation’s product overview.

Additionally, the higher-level overview often gets more into pre-sales territory than many technical writers are comfortable with. In this space, you’re trying to tell the who, what, and how of the product in a way that resonates with user pain points. In The importance of “how” in developer messaging, Matthew Revell argues that developer messaging needs to start with the what and how before the why. He touches on the need to build confidence with your audience, to align your goals with theirs. Revell says:

The origin myth of a product provides a framework that enables people to form their own feelings and thoughts about it. Without ‘why’ there’s no developer community, no champions, no advocacy.

Origin myths are not typical content that technical writers create. For example, you will not find a tutorial on origin myths in any technical writing handbook.

Developer messaging focuses on building trust with users, finding an emotional connection with them, addressing the developer journey, and telling the product story. Most tech writers don’t think about this type of content in docs — this is the land of content marketing. For example, suppose you worked as a technical writer for Red Bull. Your primary task would be to describe the product’s ingredients, not to construct a story about Red Bull being the drink of extreme sports enthusiasts, for as helicopter skiers and daredevil mountain bikers.

As such, if there is not a marketing layer for the product, tech writers are unlikely to create one because this space entails writing that tech writers might not want to dabble in. Or the marketing layer might fully address questions, so they don’t need to be redundantly handled in docs.

However, any good content strategy should have alignment with each content touchpoint, from pre-sales to post-sales. In Principle 8: Align the product story with the user story, a series on how to simplify complexity, I argued that products often fail because the story the company tells doesn’t align with the story the user tells. Developer docs have the added complexity of having three stories: a company story, an end-user story, and a developer story. If all three groups are playing off different stories, the product likely won’t succeed.

Even if a technical writer’s job is to focus on the how and what, more than the why behind the product, technical writers should have a larger sense of product story that helps structure and direct the technical content. Ideally, the shape of documentation should be constructed around the developer journey, and that journey should connect with the product story.

Look to see if marketing content covers the higher-level content needs in the documentation overview. If so, you could simply link to the marketing content, or alternatively, put a more technical, matter-of-fact spin on the same content. Either way, think about the developer’s journey and story they tell themselves, and consider using this journey/story to shape your documentation.

Cause 6: Tech comm buys in to the “reading to do” paradigm for docs, minimizing the need for longer conceptual docs

Another reason for lack of product overviews, even when outsiders like tech writers create the product docs, is due to tech comm’s strategy preference for task-oriented docs. There’s a strong belief among most tech writers that users turn to docs only when they have a task-related problem they’re trying to solve.

As a result, docs are usually problem-oriented, focused on what users want to do and achieve. Conceptual docs are often seen as a sideshow to the task-oriented docs. This idea is so pervasive, it hardly needs explaining. The hallmark of good technical docs, most tech writers believe, is a list of numbered steps that takes users through a complex task.

This more action-oriented, experiential approach to learning has its roots in a movement called “minimalism” that John Carroll, author of the Nurnberg Funnel identified in the 1980s. Describing John Carroll’s minimalism approach, scholars David Farkas and Thomas Williams write:

The premise behind minimalism is that people learning to use computer software are impatient, mentally active, and curious. They want to begin right away getting their work done; they want to exercise their problem-solving abilities; and they are apt to utterly reject or diverge from highly constraining instruction such as tutorials. Training material, therefore, must not impede the natural impulses of computer users, as systems approach documentation does. It should be as brief as possible, support the accomplishment of real work, help leaners recognize and recover from errors, and, when possible, permit non-sequential reading. Such documentation cannot be generated mechanically from a theory of instruction but requires careful attention to the needs and behavior of the intended users of the software and reiterative testing of the design. (See John Carroll’s The Nurnberg Funnel and Minimalist Documentation. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, Vol. 33, Nov. 4, Dec 1990.)

If people are always anxious to do tasks, not read conceptual overviews, then why spend time on these conceptual overviews? What purpose do they solve when users just want a list of steps for the task they’re trying to perform? With this mindset, the product overview gets shortchanged.

Don’t get me wrong — I support task-oriented docs and agree that it’s generally the right approach. There’s merit behind experiential, action-oriented learning (which is explored more in the Reasons why getting started tutorials fail or don’t exist). Explanation docs without a hands-on sense of the product often fall flat. We need context and experience with a product to better understand it. If you try to learn something without first tinkering with the product, it’s hard because names don’t mean much unless you have something to hang them on. I learn best by mixing the two experiences — tinkering and reading, back and forth.

But task-oriented docs often swing too far toward tasks, resulting in minimal or anemic overview information. When that happens, you often end up confusing users with various tasks and no higher-level content that helps their decision-making about which tasks to follow and why.

In research about how developers use APIs, researchers have identified “opportunistic behaviors” (try-first), “systematic behaviors” (read-first), and hybrids of the two. When users are observed, there’s much hybrid behavior than solely opportunistic or systematic. Just because you might be an opportunistic user, it doesn’t mean you always skip conceptual explanations — it’s just that you might not start with concepts. A hybrid reader might start with code, trying it out on their own, and circle back to the introductory conceptual information when the code doesn’t work as expected.

Deciding to cater to one type of behavior at the expense of the other might not be practical, since the learning behaviors and approaches seem to be in constant flux.

Remember that user behavior isn’t night and day when it comes to opportunistic versus systematic behavior. Users flip back and forth between these two modes as needed. As such, try to link between the task-based topic and concepts where relevant to accommodate this fluctuating behavior.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.

69/167 pages complete. Only 98 more pages to go.