My 2025 trends predictions for tech comm

This post is also available as an AI-generated podcast from NotebookLM:

Listen here:

- Analyzing my changelist history

- Alternative reasons for more CLs

- You focus more on what you track

- Predictions about hiring

- Trends with APIs

- Lack of interest in AI

- Innovator’s dilemma

- My prediction for 2025 with AI

- Conclusion

As a general note, understand that this post represents my opinion only and isn’t backed by rigorous data, or even much data in some cases. My data is mostly my experience, which should count for something given that I’ve been a tech writer for 20 years and work at a big tech company. But even so, it’s just one person’s experience at one company in one part of the world.

Analyzing my changelist history

As a way of reviewing 2024, I looked at my changelist history in 2024. At Google, when you publish anything, you submit what’s called a changelist (CL)—similar to making pull requests in Git. Changelists, which can easily be tracked and measured, include deltas for code changes, giving you a sense of your output. Because I’ve been at Google for four years (completing my fourth anniversary this year), all working in the same group (geo-based APIs for cars), I have a decent history to compare from year to year. If I look over my last four years, the CL history looks like this:

| Year | CLs authored | Lines changed | Lines added | Bugs assigned |

| 2024 | 417 | 76k | 345k | 538 |

| 2023 | 191 | 62k | 154k | 297 |

| 2022 | 145 | 6k | 196k | 174 |

| 2021 | 66 | 21k | 49k | 92 |

In 2024, as I really started incorporating AI into tech comm workflows, I had twice as many CLs and more than twice as many lines added than the previous year.

Alternative reasons for more CLs

Although it’s tempting to make an immediate takeaway about AI’s impact, it’s actually challenging to interpret this data. The problem is that many variables change each year. For example, in 2024 I started publishing docs for an SDK that included 8 separate APIs, with biweekly releases. Across all products, I published 113 release notes over the year (22 didn’t include content updates but required the reference documentation be regenerated as part of the release cycle). That’s a lot of releases for new APIs, so I’m assuming that the increased CLs are partly due to both the new SDK and the rapid release cycle.

Looking back over the other years, I’m not sure what happened in 2022 where I only had 6k lines changed but added 196k—I assume it’s from a site migration.

During 2024 I also migrated the content to another domain. All of this moving of files skews the lines changed and added, etc. We also had some team changes during this year, merging with another team. In earlier years, such as 2022, I functioned more as a tech lead with two other writers. In 2024 I played more of an individual contributor role.

During 2021, as it was my first year, I was mostly coming up to speed on the tools, workflows, products, documentation needs, and more. During my career, I’ve observed that it generally takes a couple of years at a company to become productive. Now that I’m four years in, I’ve matured in my familiarity with the company culture, workflows, expectations, stakeholders, products, etc. I’m basically at a full speed run most weeks, whereas those first two years involved more of a crawl to walk to slow jog. With four years in, I know the people, the products, etc., so I’m primed to be more productive than previous years, regardless of whether I’m using AI.

You focus more on what you track

Also in 2024, I tracked my CLs more meticulously with weekly reports because this was encouraged/required, whereas previously it wasn’t such an emphasis. In fact, due to the 6% layoffs in 2023 and the additional smaller layoffs in 2024, I was especially keen on demonstrating the value I was bringing to the company through the many CLs I was submitting. (For more on Google events in 2024, see Google CEO Pichai struggled to navigate a pressure-filled year.) Could this increased attention on CLs have caused me to generate more of them?

What you measure you also pay attention to, and the more attention I paid to generating CLs, most likely the more CLs I generated. In other words, I may have unconsciously been trying to amplify the number of CLs simply because I started tracking this metric. I find this explanation almost as plausible as the boost from AI.

As a corollary, think about food tracking and nutrition. When you start tracking everything you eat, you pay a lot more attention to it. The mere measurement of CLs could have changed my effort and focus on CLs, similar to the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle where measurement of a property changes its value. For all I know, I could have been (unconsciously) splitting up the changes into smaller CLs so that I would have more of them. I don’t think I did this, but it is a best practice to create small CLs to reduce reviewer strain on the engineers, who tap out at anything more than a page.

If I was just breaking up CLs into smaller chunks, the total code delta (lines changed/added) should have remained similar (e.g., more CLs but same code delta overall as fewer CLs), but it wasn’t. Or maybe AI made me twice as productive. Developer scripts to automate building reference docs and release notes also may have compounded the acceleration of CLs.

Like I said, it’s hard to isolate a single variable while keeping everything the same. Real data is messy. Even so, I think these stats suggest a possible productivity boost through AI. To be conservative, I’d say that my AI boosted my productivity at least 25%. AI itself frequently evolved over the year, with different tools available, different models, different policies, etc. The models available in January were primitive compared to those available in December, especially when massive token counts (~1-2 million tokens) were supported in context windows.

I also gradually increased my familiarity with best practices for using AI over the year. During 2024, I led more than 20 prompt engineering study group sessions at my workplace, in which we explored a specific prompt engineering technique related to technical documentation. (I published many of these techniques in my prompt engineering for tech docs series on my blog.) I found that the biweekly study sessions acted as a forcing function to keep me learning and experimenting with AI, which in turn fed into my productivity increase. Again, familiarity with AI techniques is yet another variable in play.

Predictions about hiring

Now for a depressing prediction. If documentation is a sweet spot for AI, and tech writers learn to produce more documentation with fewer resources, I think we’ll see companies keep technical writing hiring minimal. If companies can get the same documentation work done (or 25% more) with the same number of tech writers, they won’t be compelled to hire.

Let’s hope that companies decide to at least keep tech writer numbers minimal rather than actively reducing them as AI capabilities expand. Tech writers typically already have more work than they can ever do. For example, in reviewing the bugs in my queue at year’s end, I counted 55 unfinished bugs, even though I’ve been actively working to reduce that all year long. I’m not sure I’ll ever achieve bug zero. (Maybe when I hit bug zero, I’ll no longer be needed.)

Trends with APIs

Let’s take a break from AI for a moment. Over these past four years, I’ve also observed a strong shift towards more API-focused work. When I started at Google, most of my documentation efforts focused on a product externally referred to Google built-in (or called Google Automotive Services (GAS) by developers)—it’s like having Google Maps and other services (Assistant, Play Store) embedded directly in your car’s infotainment head unit, with no need to project from a phone.

But over the past few years I’ve seen a constant emphasis on more API-focused products, giving automakers more control and flexibility to design custom implementations based on APIs. Automakers want autonomy to create more unique, seamless, integrated experiences in cars. Especially as cars transition to electric vehicles, the digital experience inside the car takes on added importance. It can become the defining feature of an electric vehicle, given that many EV engines have similar smoothness and rapid acceleration.

So at least in the automotive domain, APIs are becoming more important and in demand than fully built, black-box-type products that lack this flexibility. I don’t know how that trend compares in other fields, but APIs provide flexibility for companies that want control over their own product design.

I’ve also seen continued interest in my API documentation course. Since making the API doc PDF available for $20 on Buy Me a Coffee’s platform, 206 people have purchased and downloaded it. In contrast, only 10 people have purchased and downloaded my Journey away from smartphones PDF. In fact, Buy Me A Coffee recently reached out to say that I’m among their top 2% of online sellers. I made a few small improvements to the API course content this year, updating the Redocly tutorial (due to their many new releases), the Stoplight tutorial, and reorganizing the introduction. I also split off the AI content into a separate section of my site because I found I was just tacking on new posts without a strong tie-in with the API documentation course (already ~ 900 PDF pages).

APIs were a trend I noted back in 2016, and the trend seems to have continued. However, to comment on whether API usage itself is growing, or which type of APIs are becoming more popular, I’d need to dedicate time to analyzing reports such as Smartbear’s State of API survey. I’ll save that work for another post.

Despite this continued API focus, traffic to my site has decreased quite a bit this year. During 2024 there were only 577k page views, down 42% from last year. Only 5 of the top 10 pages are from my API doc site, whereas previously almost all the top 10 pages were from the API doc site. So maybe the API world has shifted a bit, but this is something I need to dive into more in a future post.

Lack of interest in AI

API and AI trends seem somewhat intertwined: because APIs are so technical, it’s natural for tech writers to draw upon AI to help with API-related documentation tasks. So let’s return to some more AI trends. In my colleague Kayce Basques’ 2024 Machine Learning Review (For Technical Writers), Kayce writes:

Continued lack of interest in GenAI

It seems that most (~60%) technical writers (TWs) are not interested in integrating GenAI into their work practices for a variety of reasons:

- Fear of accidentally automating themselves out of a job

- Environmental concerns

- Copyright issues

- A deep disdain for hallucination

I expect adoption of GenAI in technical writing to continue to be slow in 2025 because I don’t think these issues will be solved in 2025.

I’ve observed similar trends with tech writers expressing both lack of interest and even contempt for AI. For example, I remember seeing a Reddit thread where someone complained about “having [AI] shoved down my throat by mostly non-writers.”

Despite running many prompt engineering study group sessions at my work, there are only a handful of regular participants out of the hundreds of tech writers who might possibly attend. It’s not so different from another AI techcomm enthusiast group I participate in—each week it’s the same faces. Always enthusiastic, but largely in a bubble that contrasts with the general apathy shown by most other tech writers.

Is it apathy or something else? It’s hard to interpret the absence of participation. In The AI-Driven Leader: Harnessing AI to Make Faster, Smarter Decisions (an audio book I’m currently listening to), Geoff Woods explains:

In my initial plan I’d assumed three things: (1) leaders believe AI is the future; (2) leaders believe their business will adopt it, and (3) leaders are actively pursuing AI adoption. But after conducting over 200 one-on-one interviews with executives, I was stunned by my findings. 100% of them believed AI is the future. 100% believed their business would adopt AI. Less than 5% had done anything to bring AI into their organization. This disconnect became the driving force behind this book.

Throughout my interviews I discovered that although executives acknowledged the need to adopt AI eventually, three main obstacles held them back: (1) they were too busy with all the existing demands of the business; (2) they didn’t understand what AI was or how it could help them; (3) no one had shown them the simple path to go from zero to one with AI in a way that would create value for them.

In other words, it might not be apathy about AI but rather the fact that tech writers are too busy to figure it out. If I surveyed tech writers about their attitudes towards API, maybe 100% would believe it’s the future and that they’ll adopt it, but perhaps only 5% have doing any serious experimentation or learning. Incorporating AI into existing tech comm workflows isn’t straightforward or intuitive. Woods continues:

I realized the simple path to go from zero to one with AI wasn’t weaving it into products or services or boosting operational efficiency. It was putting AI into the hands of leaders so they can experience its incredible value firsthand. Once a leader believes in AI’s potential, then they can drive it through their company. This would not come from showing them how to write a better email. That is not what drives business value.

Similar to Wood’s conviction that AI’s transformative potential doesn’t come from simple tasks like writing emails, tech writers will likely find conviction when they go beyond fixing simple grammar errors to using AI for developing conceptual articles, generating release notes, or understanding connections across disparate API products.

One of my colleagues compared using AI like learning to play an instrument—it’s one thing to have an intellectual understanding about the instrument and notes, but knowing how to play an instrument well is entirely different. It takes practice, experimentation, learning, diligence, and time. Maybe too many tech writers feel that AI should provide a push-button solution to creating documentation effortlessly (a misguided perception based on too much AI hype). When pushing that button doesn’t magically produce great docs, perhaps they become cynical and dismissive?

In addition to the musical instrument analogy, I’ve come to see AI tools as power tools for technical writers. If you gave me an “impact driver” (I’m not a handyman), I wouldn’t know what to do with it over a drill or screwdriver. But in the hands of a skilled contractor, the tool makes them more capable and efficient.

Imagine hiring someone to redo the roof on your house and they show up with a hammer as their only tool. The project would likely be tedious. In the same way, a tech writer who shows up to an API-focused engineering team with paper and pencil would be met with a lot of questionable looks.

In the hands of skilled technical writers who know how to use AI, the many API tools can boost and amplify documentation work. In the hands of people who don’t know how to make use of AI, the tools might seem unnecessary and clunky.

Innovator’s dilemma

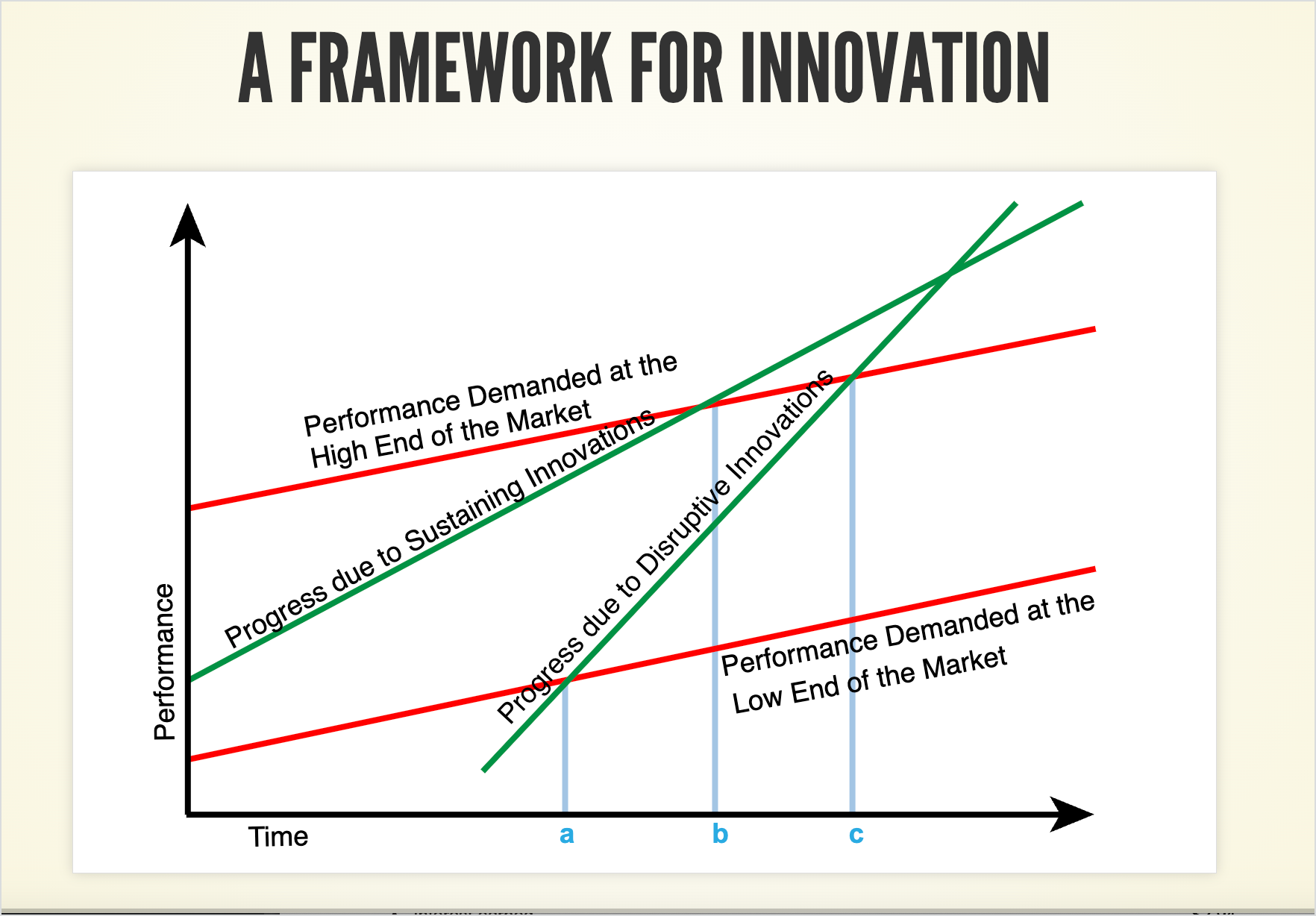

In discussions about AI, one reference not mentioned enough is the innovator’s dilemma. (I wrote about the innovator’s dilemma briefly in Sustaining and disruptive innovations. I also spoke about it during my 2015 tcWorld India keynote—the recording is here).)

As a key example of the innovator’s dilemma, think about when video streaming just started to appear on scene—it was expensive, buffered constantly, glitched out, etc. Watching a video stream of a multi-gigabyte video file on a slow internet connection must have been laughable. Hence Blockbuster passed on the acquisition of Netflix. But streaming was quickly getting better, and before long, streaming overtook DVD rentals and Blockbuster became a classic example of a company that missed key innovations and became obsolete overnight.

Compare AI to the early days of Netflix. Sure, there are hallucinations and glitchy models. Policies are unclear and riddled with questions and concerns. The tools themselves often hang and aren’t reliable. Models frequently change and this might affect previous prompt outputs that were working. But AI’s progress trajectory is angling upward a lot faster than the current progress trajectory of sustaining innovations. In the sustaining innovation category, DITA transitioned from 1.2 to 1.3. A few new browser-based platforms emerged with better search capabilities and interfaces. But not much else has evolved with sustaining innovations.

If you ignore the disruptive innovation too long, its accelerated progress trajectory will catch up to the sustaining innovation’s trajectory and surpass it. When those two trajectories intersect, you want to be on the side of the disruptive innovation to avoid being left behind like Blockbuster, Kodak, Blackberry, or the many other examples of once dominant companies that had quick exits.

In a nutshell, the dilemma about innovation is that in the beginning phases, disruptive innovations have a lower progress bar than current technologies. As such, we should be more forgiving about their current shortcomings. The following diagram (from my earlier referenced slides) shows this:

My prediction for 2025 with AI

Based on my own experiences using AI, which have been positive and productivity boosting, here’s my prediction for 2025. In 2025, more tech writers will discover how useful AI can be in writing, editing, and publishing technical documentation. They’ll learn to avoid hallucination traps, identify prime use cases where AI excels, and be given more of a greenlight to use AI tools. Those technical writers who initially had poor experiences with AI will find that, with these more powerful AI models and tools available, their previous experiences no longer hold sway and they’ll become more optimistic around AI.

This change in sentiment will continue gradually into mid-2025 but will steadily pick up steam in part driven by the AI race among the big tech companies, each pushing out more sophisticated, capable models. By the end of 2025, most tech writers will see the integration of AI tools as essential in their tech writing workflows.

Employers will also start looking at AI skills in the hiring of technical writers. Employers will want technical writers to demonstrate awareness and competence in using AI tools, in part because employers will expect technical writers to cover more ground and write, edit, and publish more tech docs. That level of productivity won’t be possible with the previous tech writer model of hand-writing docs.

As I noted earlier, I think hiring will continue to be slow through 2025, continuing more or less similar hiring trends as present. Companies will expect tech writers to make more docs with fewer resources. In some cases, tech writers will require developers to produce drafts (also with AI’s help), and tech writers will function as editors and publishers. Tech writers will make stylistic adjustments, identify how the content fits into the larger landscape (such as terminology harmony), and focus on information architecture, flow, and analytics.

Developers still won’t take over technical writing, though, because as I noted in my post titled To establish value, focus more on high priority projects, developers aren’t evaluated based on documentation contributions but rather by their code contributions. Developers will also be squeezed to produce more code in shorter timelines, and they’ll continue to offload documentation tasks to technical writers, continuing the trend of specialization. Additionally, despite the many AI tools available to developers for writing docs, I haven’t seen any noticeable engagement from developers writing documentation, except from a select few engineers, often the junior ones.

During my past year, I observed how I covered more ground with the same number of resources. Previously we had two technical writers working in my auto space; mid-year, the other tech writer transitioned to cover other areas that lacked tech writing coverage outside of auto. I relied more deeply on AI to help fill the gap. Any new hires usually go to engineers and product managers who have also been stretched thin.

I also automated some publishing tasks through more sophisticated scripts (see my post Creating scripts to automate doc build processes as well as Ellis Pratt’s recent podcast Trends for 2025 and beyond in technical writing). The main products I support have biweekly and weekly releases, and I’m regularly running these scripts to regenerate docs. I’m using file diffs to help write release notes. And now I’m also using scripts to identify missing reference documentation and assign doc bugs to engineers. All of this is made more possible through AI.

Conclusion

I’ve covered a lot of ground in this post. It’s long because I’m thinking through issues and sorting them out in my mind. What can we do to prepare and harness AI in 2025? I’m going to keep the same trajectory as 2024: continuing with my regular prompt engineering for docs study group sessions at work and blog series , which will drive more posts in this category on my blog. I’ll keep experimenting and adding to the workflows where I can incorporate AI. I’ll continue tracking and monitoring my CLs and see if my trajectory corresponds with similar trajectories of those in my prompt engineering study group.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.